the panthers controversy, or: the abbreviated life and chaos of marcus caelius rufus

the tldr: he served cunt

This is a long one, but I hope you’ll read it! The letter translations in this essay are from Shackleton Bailey; all other translations included here are my own.

I’ve mentioned the Pro Caelio in a few other newsletters, and it’s starting to feel like an injustice to keep doing that without talking about the man behind the title. I don’t mean Cicero, its author, as much as I dearly love to yap about him: Pro M. Caelio Oratio translates to “Speech for Marcus Caelius.” It was a defense speech delivered in the Roman law courts on April 4, 56 BCE, when Cicero was serving as Caelius’s lawyer against charges that included violence, poisoning, and murder. More colloquially, then, the Pro Caelio is often referred to as “In Defense of Caelius”—but let’s go a little deeper. Who was Caelius?

our hero

I am so glad you asked, dear readers.1 Marcus Caelius Rufus was born into a wealthy family in 82 BCE,2 and by his late teens he had become well-integrated into public life as a protégé of both Cicero and the future triumvir Crassus.3 With this arrangement, he was akin to a rhetoric and political studies intern, following them around all day and observing how they navigated the courts and Rome’s otherwise cutthroat political arena. After briefly becoming tangled up in the Catilinarian conspiracy during his reckless youth, in 59 BCE Caelius achieved his first big solo victory as a lawyer, winning a prosecution case against the former consul Antonius Hybrida. Cicero later wrote of his once-student:

His delivery [of speeches] was brilliant and commanding, and his style was especially recognized for its sophistication and wit. He made some important public speeches and undertook three merciless prosecutions, all of which arose from political rivalries.4

None of his complete orations have survived to the present day. Based on a surviving fragment of his speech against Antonius, though, his prosecution style was sharp and ruthless. He excelled at painting rich, vivid scenes with his rhetoric and dissing his opponents so badly that they must have wished to die. And that’s the important thing here: if Caelius really was a poisoner and a murderer (and we’ll get to those accusations soon!), he must have been the cuntiest man ever to be so accused. The consensus of every source—ancient or modern—is that he was both insanely charming and wildly good-looking. Gaston Boissier wrote:

He was dreaded for the satirical sharpness of his speech. He was bold to temerity, always ready to throw himself into the most perilous enterprises. He spent his money freely, and drew after him a train of friends and clients. Few men danced as well as he, [and] no one surpassed him in the art of dressing with taste…

And T.P. Wiseman really drove the point home:

He was strikingly handsome, a dandy in his dress, and with a taste for extravagant social life. He loved laughter, and his wit was cruel: there was no better joke than the expression on the face of an enemy he had done down. Quarrelsome, violent, generous, passionate, in a later crisis he defined his own motives as good intentions overcome by anger and affection; what counted with him was resentment and exasperation. He could sum up other men’s failings as ruthlessly as his own, and his insight into character and motive made him a brilliant interpreter of the politics of his day.

And if you like redheads, congratulations, this is the Roman for you: the cognomon rufus literally means “red.”

By his own admission, Caelius was a lazy letter-writer, but we are fortunate to have seventeen surviving letters he wrote to Cicero between 51 and 48 BCE (and nine that Cicero wrote back to him): they are preserved in the collection broadly known as Cicero’s Epistulae ad Familiares, “Letters to Friends.” It is here that we get the strongest sense of Caelius’s character. While he was certainly intelligent and politically astute—he sometimes bordered on politically prophetic—he was also “bright, happy, witty, frivolous, and doubtless lovable… Cicero himself now and again catches the infection, and tries (in vain) to write in the same frivolous manner…”

Their connection continued long past Caelius’s student-intern days and blossomed into a genuine friendship. His letters are underpinned by a respectful tone—Cicero was at least eighteen years older, and Caelius would have been mindful of their mentor/protégé dynamic—but they radiate affection and intimacy. In 51 BCE, Caelius wrote to him:

When you were in Rome and I had any free time, I was sure of employment the most agreeable in the world—to pass it in your company. I miss that not a little. It is not merely that I feel lonely; Rome seems turned to desert now that you are gone. I am a careless dog, and when you were here I often used to let day after day go by without coming near you. Now it’s a misery not to have you to run to all the time.

The affection was mutual. “The letters [between Cicero and Caelius] indicate a friendship expressed in hearts and flowers,” wrote Amy Richlin. “The tone is very unlike what Cicero uses to his age-mate [and closest friend] Atticus, or even to his wife, except when he is pining away for her from exile.” In his own words, also from 51 BCE: My dear Rufus, you are fortune’s gift to me… I have never sent a letter home without another for you, than whom nothing in life is dearer to me or more agreeable. In a modern alternate universe, they would be at brunch, drinking mimosas and gossiping: I am worried about affairs in Rome… but the most worrying thing of all is that, whatever there may be to laugh at in all this unpleasantness, I cannot laugh at it with you.

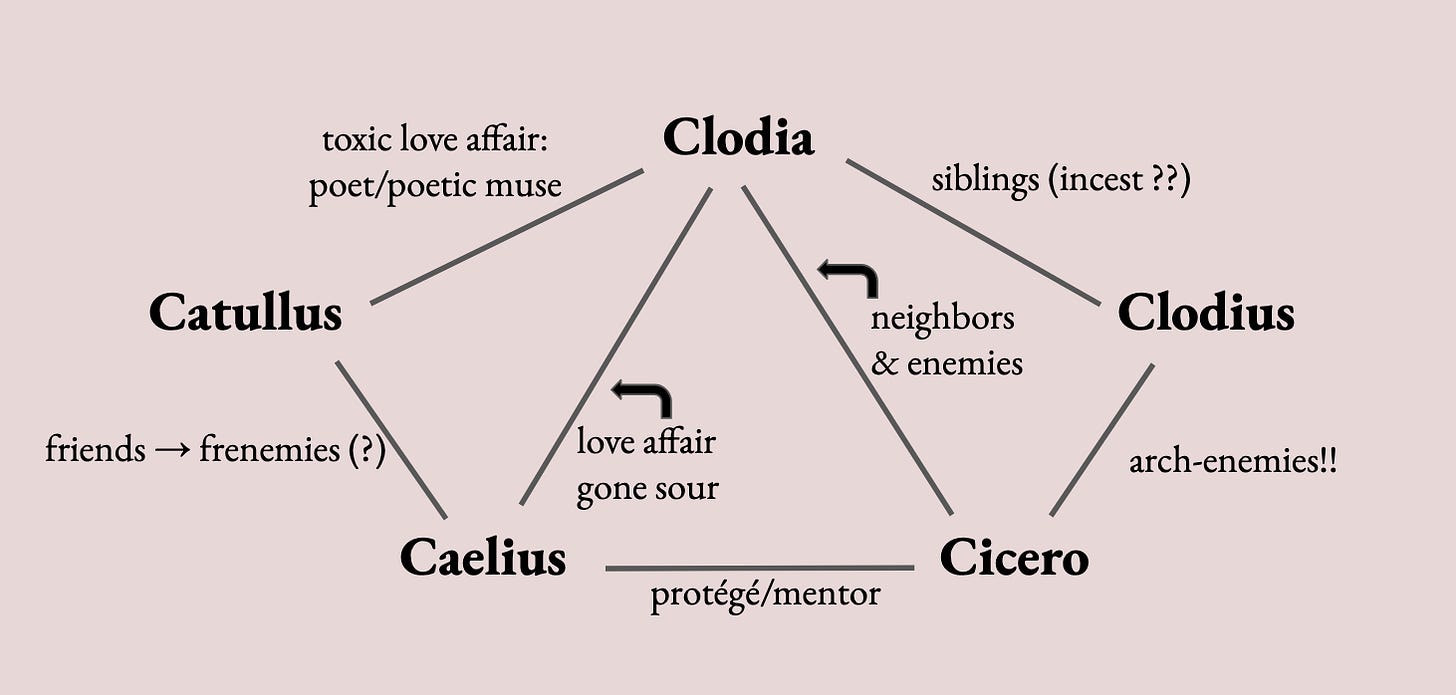

But Caelius, so noted for his flamboyant social life, had other connections beyond Cicero, many of whom would become important players in his story. Let’s back up to 57 BCE, just a couple of years after his first big court win. Caelius, then about twenty-four years old, moved out of his father’s home and rented an apartment on the Palatine Hill. Ostensibly, this was to be closer to the political hub of the Forum; in practice, it may have been just as much about living in a fashionable, wealthy neighborhood brimming with fashionable, wealthy people. It was here—or through his existing friendship with the poet Catullus—that Caelius met Publius Clodius Pulcher and his sister, the infamous Clodia Metelli. Clodia, of course, is also known to us from Catullus’s poetry by the pseudonym Lesbia.

I’ll cut to the chase: when Catullus was agonizing over Lesbia cheating on him with other men, Caelius was one of the other men. “We have every reason to believe that Caelius found it easy to accept Clodia’s favors and money,” Merle Odgers wrote. The affair was probably short-lived—but it ended badly, and the ripple effect would be felt for months to come. On the merely depressing side was the emotional blow to Catullus. We can’t be certain, but Caelius may be the Rufus addressed in Catullus’s c. 77:

Rufus, whom I believed to be a friend—uselessly, and in vain

(in vain? no, in fact, with a great and terrible price)—

in this way you crept up to me and, burning up my guts,

you tore away every good thing of ours from miserable me.

You snatched them away! Alas, alas—you, cruel poison of my life.

Alas, this plague of our friendship.

The other consequence was the Pro Caelio.

his trial

The Pro Caelio is situated within a swirling vortex of politics, and it’s just not possible to unpack all of it within this essay. What you need to know is that Caelius’s trial was not purely political: although it did have political overtones, it “stemmed from personal animosities and was fought on a personal level.” Clodia and her brother Clodius, so recently estranged from Caelius, were heavily connected to the prosecution.

The main charge was vis, political violence—a very serious accusation—but Caelius was accused of five specific offenses in total: inciting violence in Naples; assaulting Alexandrian diplomats in Puteoli; damaging the property of a woman named Palla; murdering the philosopher Dio (with money borrowed from Clodia); and attempting to murder Clodia via poison.5

At the trial, Caelius spoke first with a speech in his own defense, followed by his former mentor Crassus. Cicero, armed with the Pro Caelio, spoke last. A full breakdown of the speech can be found here. (It’s entertaining but entirely founded in misogyny, so be warned.)

Was Caelius guilty of murder, real or attempted? The Pro Caelio certainly wants us to believe the answer is no, and that probably was the truth—at least as far as serious criminal offenses went. The prosecutors also threw in accusations about general immorality and bad behavior. Those were probably closer to the mark, and Cicero knew it. His strategy is apparent in the very first paragraph of the speech:

A young man [Caelius] with a brilliant intellect, a diligent work ethic, influence, and charm is accused by the son of a man whom Caelius himself has prosecuted before and is preparing to prosecute again6—and moreover, he is being attacked by the resources of a harlot.7

As much as it was a speech in defense of Caelius, it was also a speech that revolved around attacking Clodia. If you listened to Cicero, those two things were inherently connected: the jurors were too focused on convicting Caelius when the real villain, Clodia, had been there all along! The Pro Caelio as a whole can be broken down pretty nicely into three big themes:

Clodia smear campaign. “The list of accusations, by its length alone, had to leave many jurors with strong suspicions of guilt, and it is clear that Cicero wished to divert their attention from Caelius by shining the spotlight on Clodia.” The gold came from Clodia; the poison was meant for Clodia—wasn’t that suspicious? She was bitter over Caelius ending their affair and she wanted to get revenge. She was petty, slutty, dishonorable, a shame to her family name, and discreditable, too—so the charges were also discreditable, and completely ridiculous. A poison charge, coming from a woman whose own husband had so recently died so mysteriously!

Boys will be boys. Had Caelius occasionally been wild and reckless? Sure, said Cicero, but I could mention the names of many men of the highest rank and honor—some of whom were well-known for excessive licentiousness in their youth, others for excessive luxury, vast debts, indulgences, sexual appetites—men whose faults were later covered up by so many virtues that anyone who wished could defend them with the excuse of youth. Basically—when you’re young, heedlessly sowing your wild oats is fine.

Caelius is so, so handsome. This is not an exaggeration.

As James May wrote: “Of course, the admission that the affair [with Clodia] even took place implies that Caelius has himself indulged in questionable behavior. Cicero is faced with adopting a double standard… justifying Caelius and vilifying Clodia for precisely the same actions.” Luckily for him, society has always loved a double standard. After Cicero blackened Clodia’s name—impersonating her disapproving ancestors, branding her a prostitute, tossing around sibling incest jokes8—he had no trouble dismissing the charges she’d brought against Caelius. And as for the affair, Cicero said: poor judgement it may have been, but it was only a dalliance and now it’s out of Caelius’s system. He has outgrown that wild, irresponsible stage of youth, and now he’s ready to embark upon the straight and narrow path and make honorable, illustrious contributions to society—just like his surrogate father, Cicero!9

And as for Caelius being so, so handsome: there really are an astonishing number of references to his good looks in this speech. Maybe he’s been a bit of a playboy, Cicero acknowledged, but as for the criticisms passed on his morals, and as for what’s been advertised by all the accusers—not criminal charges, but gossip and slander—Marcus Caelius will never carry it so bitterly that he would regret being born handsome. Indeed, it was his dashing appearance that first drew Clodia to him: You caught sight of a neighbor, a young man: his brilliant looks, his tall figure, his face and his eyes thrilled you. You wanted to see him more often. And perhaps some people might disapprove of Caelius’s fashionable clothes or his seductive perfume, Cicero said—but these are youthful indiscretions, merely what the kids are doing these days—he’ll grow out of it.10 If any of these very minor things give offense—his shade of purple, his troops of friends, his glitter, his glamour—all of these things will soon cool down; soon age, experience, and time will soften it all.

The speech worked. Caelius was acquitted of all charges (although some historians have suggested that he had been, at least peripherally, involved in Dio’s murder). His personal life vanishes from the historical record after his trial: everything we know about him in the eight years between 56 and 48 BCE are about his political activities. He began to focus on climbing the political ladder, the cursus honorum—but even then, Cicero’s promises about age, experience, and the passage of time would not come to pass.

the panther letters

Let’s turn back to the Caelius-Cicero correspondence to wrap things up. A large chunk of the surviving letters we have between them—fourteen from Caelius to Cicero, and seven from Cicero to Caelius—were written in 51-50 BCE, while Cicero was serving a governorship term in Cilicia (modern-day Turkey). Moping over being cut away from the political hub of Rome, he tasked Caelius with sending him regular digests of what was happening in the city. Cicero certainly got his political news, and sometimes even bits of gossip11—but a standout feature of the letters is the ongoing Panther Issue.

Caelius had been elected to the office of curule aedile in 51 BCE. In name, curule aediles were responsible for maintaining and regulating civic infrastructure; in practice, anyone elected was more interested in gaining notoriety and popularity by hosting public games (think gladiator contests or animal fights). This was an expensive business. They were expected to finance the games out of their own pockets, and politicians often sunk themselves into debt putting on a show. It’s no wonder, then, that Caelius saw his window of opportunity—Cicero’s tenure in Cilicia meant exotic panthers! for free!—and pounced on it.

The first mention in the letters is June 51 BCE, clearly alluding to some former, in-person conversation: As soon as you hear I am designate [officially elected to the office of aedile], please see to the matter of the panthers.

Again in August: I am anxious to make you realize my strong personal concern in that matter. Likewise about panthers—please send for some from Cibyra and have them shipped to me.

And in September: In almost every letter I have written to you I have mentioned the subject of panthers. It will be little to your credit that Patiscus has sent ten panthers for Curio [Caelius’s friend, a tribune that year] and you not many times as many… Do be a good fellow and give yourself an order about it. You generally like to be conscientious, as I for the most part like to be careless. Conscientiousness in this business is only a matter of saying a word so far as you are concerned, that is of giving an order and commission.

And several months later, in February, flavored by exasperation and the quick temper Caelius was so well-known for: It will be little to your credit if I don’t have any Greek panthers.

Cicero, for his part, was exasperated too. Despite his Caelius bias, he clearly had no interest in coordinating panther-hunting (he was, during his governorship, busy navigating a war with neighboring territories). In April, he wrote back:

About the panthers, the usual hunters are doing their best on my instructions. But the creatures are in remarkably short supply, and those we have are said to be complaining bitterly because they are the only beings in my province who have to fear designs against their safety. Accordingly they are reported to have decided to leave this province and go to Caria. But the matter is receiving close attention . . . Whatever comes to hand will be yours, but what that amounts to I simply do not know.

We don’t have Caelius’s reaction to such a silly excuse (the panthers developed human-like sentience and emigrated from the province??), and we also don’t know whether he ever received his panthers.12 By 49 BCE, conversation was turning towards the Caesar-Pompey rivalry and the brewing of civil war. Rome’s elite were choosing sides. Cicero, a staunch supporter of the Republic and traditional values, chose Pompey; after much fence-sitting, Caelius—whether for a genuine desire for social reform or simply because he was an opportunist—chose Caesar. He wrote to Cicero:

I don’t suppose it escapes you that, when parties clash in a community, it behooves a man to take the more respectable side so long as the struggle is political and not by force of arms; but when it comes to actual fighting he should choose the stronger, and reckon the safer course the better.

The logic, however opportunistic, was correct. Caesar was the stronger side and the safer one. (Cicero, in fact, would switch his own allegiance within the year.) In February 48 BCE, smack in the middle of heightened conflict, Caelius wrote to Cicero in one of his last surviving letters:

I can't explain matters to you unless we meet, and I hope that will soon take place. For as soon as he has driven Pompey out of Italy, Caesar has resolved to summon me to Rome: and I look upon that as good as done, unless Pompey has preferred being besieged in Brundisium. Upon my life, the chief motive I have for hurrying there is my ardent desire to see you and impart all my thoughts. And what a lot I have! Goodness! I am afraid that, as usual, I shall forget them all when I do see you.

But Caelius and Cicero would never meet again. Despite his correct selection of the winning side, later that year Caelius grew irritated with Caesar over perceived slights and political disagreements—and in one last instance of poor judgement, he joined a rebellion against him. This time, the mistake was fatal. Caesar, in his Commentarii de Bello Civili, recalled Caelius’s death:

Caelius, having set out (for Caesar, he said), reached Thurii. There, he tried to rouse some men from the town and offered money to Caesar’s Gallic and Spanish cavalrymen, who had been sent there for garrison duty. They put him to death. And so the beginning of a serious movement, which had kept magistrates busy and kept Italy anxious about the state of the times, came to a quick and easy end.

It was also the end of Caelius, reduced to a single paragraph: “the logical end of one who had been a playboy of politics,” wrote Merle Odgers. And as the rhetorician Quintilian wrote in 95: “He deserved a wiser mind and a longer life.”

Of course we all love chaos and a man who knew how to serve cunt, but I admit I had another motive for writing this essay. In 51 BCE, Caelius wrote to Cicero: Now I have a favour to ask. If you are going to have time on your hands, as I expect you will, won’t you write a tract on something or other and dedicate it to me, as a token of your regard? You may ask what put that into my tolerably sensible head. Well, I have a desire that among the many works that will keep your name alive there should be one which will hand down to posterity the memory of our friendship. I hope I have contributed something towards that wish.

Nobody actually asked.

This date is from Pliny, who also says that Caelius was born on May 28. This means he was a Gemini, to which I can only say: that would explain so much.

Marcus Licinius Crassus would later become the third prong of the First Triumvirate with Caesar and Pompey. Before that, he was best known as being kind of an asshole and also the richest man in Rome (and doesn’t that sound familiar these days?).

This is from Cicero’s Brutus, a history of Roman oratory. The praise of Caelius the prosecutor is hilariously followed by the opinion that he was mediocre as a defense lawyer: not great, but “indeed quite tolerable.”

Remember that Catullus also called him “poison of my life” in c. 77… which could mean nothing!

A seventeen-year-old named Atranius was Caelius’s main prosecutor. Atranius’s father had previously been dragged into court by Caelius.

Clodia. From Michael Volpe: “The use of meretrix, prostitute, to refer to Clodia was a bold move that tells us a great deal. Normally this would have been a grievous insult, but Clodia’s bad reputation made it possible for Cicero to foreshadow here at the beginning the manner in which he intended to deal with her later in the speech.” It goes without saying that she has been dealt a brutal hand in the way of historical legacy: all we know of her comes from men who despised her.

The Pro Caelio is the source of Cicero’s most well-known and most distasteful Clodius/Clodia incest joke. “If I didn’t have a quarrel with that woman’s husband—brother, I meant to say, her brother! I am always making that mistake.”

The comparision is about making illustrious contributions to society. The idea that Cicero ever had a wild, irresponsible youth is frankly laughable.

“Real men” in Rome wore plain, somber colors: if you looked boring, you were doing traditional masculinity right. The worst case scenario was appearing “effeminate.” Colors, fabrics, jewelry, shoes, and perfumes were all sources of insults and vitriol in public spaces.

Caelius relays that a guy has been caught three times in two days committing adultery and then refuses to share any other juicy details: Where? Why, just the last place I should have wished—I leave something for you to find out from other informants! Indeed I rather fancy the idea of a Commander-in-Chief [Cicero] enquiring of this person and that the name of the lady with whom such-and-such a gentleman has been caught napping.

Incredibly, however, the modern scientific name for the Anatolian leopard is panthera pardus tulliana—with tulliana coming from Tullius, as in Marcus Tullius Cicero!

omg, the relationship tree absolutely came in clutch juuuuust about the point I was starting to feel completely lost in the sauce! very much appreciated. I also LOVE all your annotations, I feel like I'm getting special hot takes and goss from each one of them :-) I really enjoyed reading this, thank u!!

Oooh Rachel, thank you so much for sharing these excerpts with us!! I think there's definitely something poetic about how he was known to have such great rhetoric and a sharp tongue, but what survived of his image to us is that he was a beloved friend, mentee, and also ridiculously handsome. I've said it before, but my fav thing about your essays truly is how nicely you paint a human picture of these ancient people. With all the interpersonal drama HOW has no one successfully adapted their stories into a GOT-esque viral TV show yet is beyond me.

(AND THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR THE RELATIONSHIP TREE.... I've been following along pretty well but all the names with C's were starting to confuse me lmaoooo)

And "won’t you write a tract on something or other and dedicate it to me, as a token of your regard?" rly got to me for some reason... if it means anything, I had no idea who Caelius was, and now I'm one of the people who carry his name in my memory :')